Just a week after the execution of Troy Davis, my team found this story.

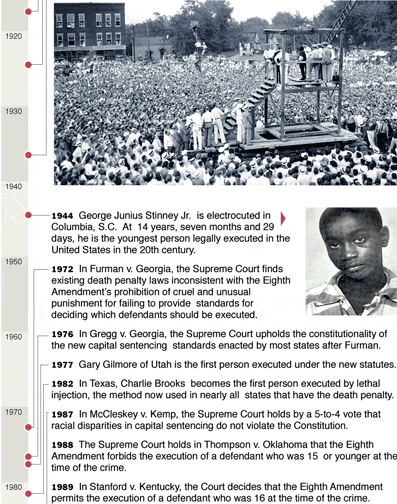

Meet George Junius Stinney, Jr. [b. 1929 - d. 1944].

He was 14 yrs. 6mos. and 5 days old when he was executed — he and holds the title of being the youngest person ever executed in the United States in the 20th Century.

In a South Carolina prison sixty-six years ago, guards walked the 14-year-old boy, bible tucked under his arm, to the electric chair.

Standing only 5′ 1″ and weighing a mere 95 pounds, the straps of the chair didn’t fit, and an electrode was too big for his leg.

But that didn’t matter. The switch was pulled anyway and the adult sized death mask fell from George Stinney’s face. Tears streamed from his eyes. Witnesses recoiled in horror as they sat and watched the youngest person ever executed in the United States in the past century die.

Stinney was accused of killing two white girls, 11 year old Betty June Binnicker and 8 year old Mary Emma Thames, by beating them with a railroad spike then dragging their bodies to a ditch near Acolu, about five miles from Manning in central South Carolina.

The girls were found a day after they disappeared following a massive manhunt. Stinney was arrested a few hours later when white men in suits came and took him away. Because of the risk of a lynching, Stinney was kept at a jail 50 miles away in Columbia, SC.

The girls were found a day after they disappeared following a massive manhunt. Stinney was arrested a few hours later when white men in suits came and took him away. Because of the risk of a lynching, Stinney was kept at a jail 50 miles away in Columbia, SC.

Stinney’s father, who had helped look for the girls, was fired immediately and ordered to leave his home and the sawmill where he worked. His family was told to leave town prior to the trial to avoid further retribution. An atmosphere of lynch mob hysteria hung over the courthouse.

Without family visits, the 14 year old had to endure the trial and death alone.

The sheriff at the time said Stinney admitted to the killings, but there is only his word — no written record of the confession has been found. A lawyer with the case figures threats of mob violence and not being able to see his parents rattled the seventh-grader.

Attorney Steve McKenzie said he has even heard one account that says detectives offered the boy ice cream once they were done.

“You’ve got to know he was going to say whatever they wanted him to say,” McKenzie said.

The court appointed Stinney an attorney — a tax commissioner preparing for a Statehouse run. In all, the trial — from jury selection to a sentence of death — lasted one day.

Records indicate 1,000 people crammed the courthouse. Blacks weren’t allowed inside.

The defense called no witnesses and never filed an appeal. No one challenged the sheriff’s recollection of the confession.

“As an attorney, it just kind of haunted me, just the way the judicial system worked to this boy’s disadvantage or disfavor. It did not protect him,” said McKenzie, who is preparing court papers to ask a judge to reopen the case.

Stinney’s official court record contains less than two dozen pages, several of them arrest warrants. There is no transcript of the trial.

Community activists are still fighting to clear Stinney’s name, saying the young boy couldn’t possibly have killed two girls.

In several cases like Stinney’s, petitions are being made before parole boards and courts are being asked to overturn decisions made when society’s thumb was weighing the scales of justice against blacks.

“I hope we see more cases like this because it help brings a sense of closure. It’s symbolic,” said Howard University law professor Frank Wu.

“It’s not just important for the individuals and their families. It’s important for the entire community. Not just for African Americans, but for whites and for our democracy as a whole. What these cases show is that it is possible to achieve justice.”

No comments:

Post a Comment